Week 39: Dinosaurs

Jack always styled himself as a dinosaur and felt a strong sense of alienation from modernity and modern literature. Does this make him different from his High Modernist peers? Or more similar?

Dear Friends,

Last week, I discussed briefly how Jack’s grief at his wife’s death brought a new emotion to his writing, in A Grief Observed and in a short poem called “As the Ruin Falls.” Today I want to look at another of his late poems—indeed, the very last poem for which we have a confirmed date—which exhibits a different sort of grief. It’s titled “Re-Adjustment.”

“Re-Adjustment”

I thought there would be a grave beauty, a sunset splendour

In being the last of one's kind: a topmost moment as one watched

The huge wave curving over Atlantis, the shrouded barge

Turning away with wounded Arthur, or Ilium burning.

Now I see that, all along, I was assuming a posterity

Of gentle hearts: someone, however distant in the depths of time,

Who could pick up our signal, who could understand a story. There won't be.

Between the new Hominidae and us who are dying, already

There rises a barrier across which no voice can ever carry,

For devils are unmaking language. We must let that alone forever.

Uproot your loves, one by one, with care, from the future,

And trusting to no future, receive the massive thrust

And surge of the many-dimensional timeless rays converging

On this small, significant dew drop, the present that mirrors all.

“Re-Adjustment” expresses something fundamental about how Jack understood himself: he believed that he was one of the last of his kind, a remnant of a bygone era.

His clearest statement of this feeling, apart from the poem above, comes in “De Descriptione Temporum,” the lecture he gave upon taking up his Cambridge chair. His ostensible purpose is to explain to his audience why his professorship spans both medieval and renaissance literature. But as he does so, he makes a more controversial claim: “I have come to regard as the greatest of all divisions in the history of the West that which divides the present from, say, the age of Jane Austen and Scott” (Selected Literary Essays 7).

To justify this position, he raises four areas of change: politics (from an emphasis on keeping the populous quiet, to stirring up mass excitement), arts (from the relatively accessible literature of the nineteenth century to the radical experiments of the twentieth), religion (what Jack calls “the un-christening” (9)), and technology (“the birth of the machines” (10)).

In the conclusion of the lecture, he tells his audience:

I myself belong far more to that Old Western order than to yours. I am going to claim that this, which in one way is a disqualification for my task, is yet in another a qualification. The disqualification is obvious. You don’t want to be lectured on Neanderthal Man by a Neanderthal, still less on dinosaurs by a dinosaur. And yet, is that the whole story? If a live dinosaur dragged its slow length into the laboratory, would we not all look back as we fled… I would give a great deal to hear any ancient Athenian, even a stupid one, talking about Greek tragedy…. Ladies and gentlemen, I stand before you somewhat as that Athenian might stand. I read as a native texts that you must read as foreigners…. Speaking not only for myself but for all other Old Western men whom you may meet, I would say, use your specimens while you can. There are not going to be many more dinosaurs. (13–14).

The lecture ends there. Jack’s tone throughout remains detached. One has to look elsewhere—in “Re-Adjustment and, I think, in his critiques of modern poetry—to feel the senses of loss and alienation that accompany this ‘dinosaur’ status.

Jack wasn’t the only writer who felt this way. For instance, we can discern a similar melancholic sense of ending in Tolkien’s idea of Middle Earth’s ages. His Third Age ends with the War of the Ring, and as the Fourth Age begins, the elves fade away, leaving the world to the dominion of humankind. His fictionalised history is intrinsically elegiac. (I should say that I haven’t studied Tolkien’s views on modernity and historical epochs deeply, but his distaste for modern literature—or non-medieval literature, to be more exact—is pretty notorious.)

But this sense of major historical change, of cultural loss and disorientation, wasn’t restricted to the Inklings.

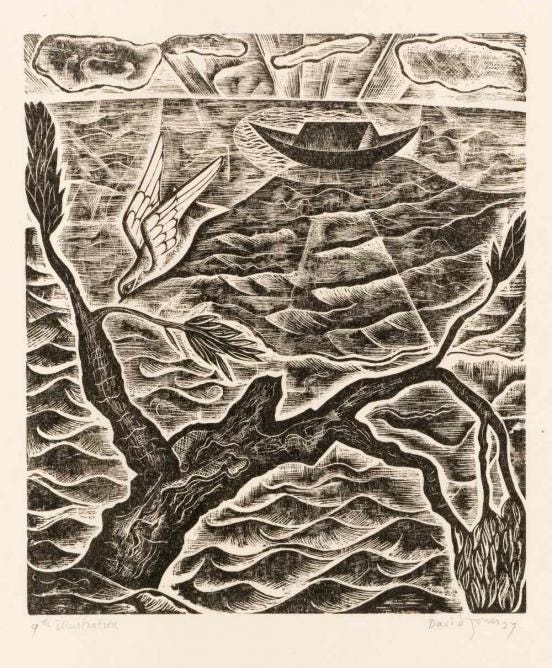

In “De Descriptione Temporum,” Jack mentions—admittedly, in passing—two examples of modern literary novelty: T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land and David Jones’ The Anathemata. I was delighted to see this, because any mention of Eliot or Jones tends to delight me, but I also find their inclusion wonderfully ironic. Because, though their poetry was stylistically innovative in a way that would not have appealed to Jack, they also both shared his sense of disorientation and dissatisfaction with modernity.

In “Ulysses, Order and Myth”, Eliot famously asserts that Joyce’s narrative innovations are “simply a way of controlling, of ordering, of giving a shape and a significance to the immense panorama of futility and anarchy which is contemporary history.” This sense of a world in chaos, a world which the artist must struggle to make sense of horrific violence and overwhelming cultural change, pervades Eliot’s early poetry, most notably The Waste Land.

David Jones was even more articulate on this subject, and he offers a theory of history very similar to the one Jack outlines in “De Descriptione Temporum.” Jones too speaks of ‘Western Man’, and the changes which he has undergone in the (more or less) two centuries from 1750 to 1950. He calls this change “The Break.”

I’m not going to quote at length from Jones, because, unlike Jack, he does not possess the gift of writing accessible prose, and so I’d have to quote several paragraphs and then write several more paragraphs to give you context for what he’s saying. I’ll give you a quick summary here—but I plan to write much more about Jones next year, so if you’re interested, stay tuned for more.

Jones is a bit cagey about the causes of “The Break”; he doesn’t give us a neat historical taxonomy like Jack does. It’s fairly clear that he considers the Industrial Revolution at least partially to blame, and perhaps the extreme, mechanised violence of the Great War as well. Whatever the historical causes, the fundamental change that troubles him is a shift from a culture that values both the utile (to simplify: things that have practical value) and the gratuitous (things valuable in themselves, like art or religious symbols), to a culture that values only the utile. He fears that art might be impossible in the modern cultural climate, and that his art in particular will be increasingly illegible as readers forget the theology, myth, and history he references.

I’m not going to evaluate Jones’ claims about history here—or Jack’s, for that matter. I’ll just say that they’re of great interest to me, because my first book focuses on nostalgia, and because they raise broader questions about modernist studies, and what it includes and excludes.

For those wondering what literary modernism is, Wikipedia gives a good enough definition:

Modernist literature originated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and is characterised by a self-conscious separation from traditional ways of writing in both poetry and prose fiction writing….The immense human costs of the First World War saw the prevailing assumptions about society reassessed, and much modernist writing engages with the technological advances and societal changes of modernity moving into the 20th century.

This definition makes it pretty clear why we don’t number Jack among the modernists: he was all about traditional ways of writing, and deeply averse to the experimental aesthetics of modernism.

When I was an undergraduate at Wheaton College, I was told by multiple people that I wouldn’t be able to study the Inklings. (This was a standard warning for Wheaton’s literature students at the time—see my recent letter on evangelicalism.) That was fine by me, because I wanted to study Eliot and Jones.

So off I went to study British modernism and religion and literature. I read a great deal of twentieth century literature for my degree, but at no point did anyone suggest I look at a single text by the Inklings. This wasn’t conscious exclusion: Jack and his set are simply not considered relevant.

Now, partially this is a question of genre and profession. If I had wanted to study the history of fantasy, which I’m sure some programs would have allowed me to do, Lewis and Tolkien would have been part of the conversation. If I had studied medieval literature, I would at minimum have read Tolkien, whose scholarship on Beowulf is the reason so many of us had to read the poem in school. But Jack and his compatriots are rarely set alongside their modernist peers.

I think this is, to some extent, a mistake. Don’t get me wrong: I’m not about to write a book on “C. S. Lewis: The Most Reluctant Modernist” (although that would be a great title, and I kind of want to use it now). Jack’s fiction and poetry do not sit easily alongside his modernist contemporaries. I’m not sure I would gain much comparing the ‘mythical methods’ of Ulysses and Till We Have Faces.

Yet it would be a mistake to think of Jack or the other Inklings as isolated dinosaurs. They’re not independent of their context, and their thinking about history in particular reflects preoccupations common in their day.

I think that modernist studies and Inklings studies have a great deal to say to each other. I’m not sure if it’s Jack’s animosity to modernism that discourages scholars from exploring these connections, or if his enduring popularity as a Christian author is a greater deterrent. But there are opportunities for exploration here.

I want to end as I began, with Jack’s poem. Go back and re-read it, if you have a moment. I take joy in knowing that Jack’s prediction is, to a certain extent, wrong:

Now I see that, all along, I was assuming a posterity

Of gentle hearts: someone, however distant in the depths of time,

Who could pick up our signal, who could understand a story.

So many people still pick up Jack’s signal and will continue to do so, I expect, for many years to come.

Still, I think his advice in the final lines is worth heeding:

Uproot your loves, one by one, with care, from the future,

And trusting to no future, receive the massive thrust

And surge of the many-dimensional timeless rays converging

On this small, significant dew drop, the present that mirrors all.

Whatever your philosophy of history, I suspect that on this Friday, in the wake of the election, we all feel uncertain about the future. I write this in mid-October, and I have no clue how I will be feeling as you read this. I won’t go back to insert some comment about the outcome here: others will be able to speak more wisely and more eloquently than I, whatever happens.

Even without such external provocations, I find that as I mature, I learn more and more the value of abiding in the present. Not that I’m good at it—but I’ve learned that I can’t live life just holding on for some imagined better future. I have to find ways to thrive in the present.

It moves me to think of Jack, mere months before his death, seeking to let go of the future, to receive the present moment in its fullness.

May you find such moments of presence this week,

Sarah

I take the same comfort too!! CS Lewis was definitely my way “in” to my love of the ancients and medieval, and study of language. May we continue to carry the torch and enchant others with these wondrous things✨

Well done, Sarah!