Deferred Responsibility

or, imperialism, the Crucifixion, and the plight of David Jones' soldiers

Dear Friends,

Just a short one for you this week, because it has been a week. The home and family parts of my vocation have loomed large—and I have a book proposal due in a couple of weeks. (Maybe someday I’ll get to tell you all more about that.)

So I’m just going to tell you about one of David Jones’ shorter poetic fragments, “The Fatigue.” It’s part of a series, all collected in The Sleeping Lord, about, in Jones’ words, “Roman troops garrisoned in Syria Palestina at the time of the Passion” (24). It depicts a group of soldiers from throughout the empire, Celts as well as Romans, intentionally illustrating “the heterogeneous composition of the forces of a world-imperium” (24). Other poems in the collection focus on the clash between Roman and Celtic culture in Britain around the same time.

For those who want to dip their toe in Jones’ poetry, I think The Sleeping Lord is a great place to start. The book is a little harder to find than In Parenthesis, but you can pick up a paperback copy for about $15 on abebooks.com or check it out for free from the Internet Archive. The poems can be dense, but they’re short and comprehensible, and they give you the flavour of Jones’ intellect and voice. And they all deal, from varying angles, with the conflict between local cultures and global empire.

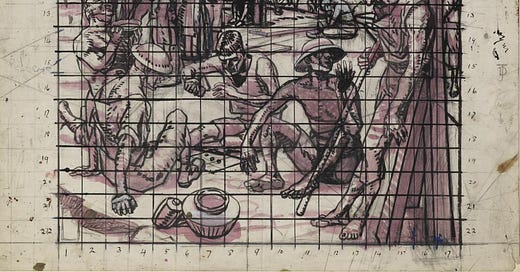

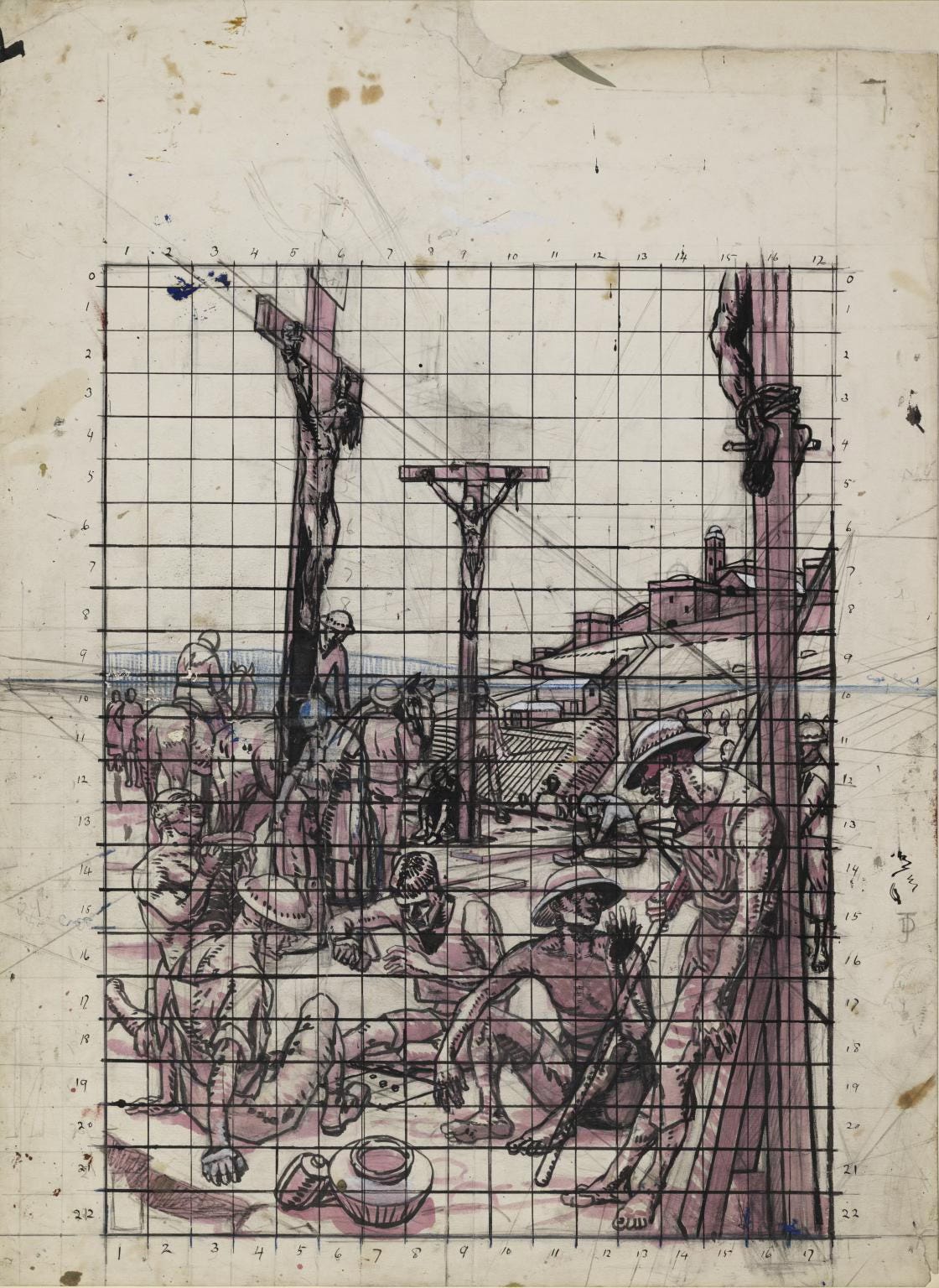

Jones visited Jerusalem in 1934, and his imagination was shaped ever after by the sense that the Roman empire into which Jesus Christ was born and under which He died—and the Roman soldiers who kept it running—might not have looked so radically different from the British empire for which Jones fought in World War I and the soldiers he fought alongside. His Roman soldiers in The Sleeping Lord sound like the British soldiers of In Parenthesis. In the image below, which might have been drawn as early as 1921, you can see soldiers in British uniform at the foot of the cross.

In “The Fatigue,” a Roman officer in Jerusalem lectures his men keeping watch on the wall of Jerusalem. “That’s how we keep / the walls of the world,” he tells them, “sector by sub-sector / maniple by maniple,” each man tending to his duty without question and without error (28). Some of these soldiers are scheduled to assist with an execution—one of many they have overseen, and yet unlike all the others. Because these soldiers are about to crucify Christ.

Jones emphasises the singularity of this event by contrasting the brusque military slang of the soldiers with liturgical and theological allusions: the soldiers “are the instruments / to hang the gleaming Trophy / on the Dreaming Tree.” They think that they’re completing an unpleasant chore, a fatigue in multiple senses of the word, even as they enact (in Jones’ perspective, and mine) the pivotal event of history.

There, in that place

that will be called

The Tumulus

you will complete the routine. (38)

The poem doesn’t end with the crucifixion, however. It ends with a detailed description of an office full of paperwork: “within the most interior room, on the wide-bevelled marbled table the advices pile and the outgoing documents wait his initials” (39). It is the tedious paperwork in this room that puts the soldiers in their place at the foot of the cross, by initiating a string of bureaucratic norms and chance events: “By routine decrees gone out from a central curia, re Imperial Provinces East Command… / by a corporal’s whim / you will furnish / that Fatigue.” (41).

There’s so much going on in this poem. In part, it’s about the machine of imperialism: the tedious bureaucracy that ends in bloodshed. My husband brings an excerpt from this poem to class whenever he discusses how the Gospels address the Roman empire.

It’s also about the peculiar moral status of soldiers, which Jones’ meditates on throughout his work. Soldiers are both individual moral agents, responsible for their actions, and tools of a larger system. Subordinating individual judgment to leaders’ commands is an absolutely fundamental part of military service. This sort of obedience can be the condition of self-sacrificial heroism, or of atrocity. That precarious ethical situation is a major theme of Jones’ work, in In Parenthesis as well as The Sleeping Lord. I wrote an article on this some years ago for a Religion & Literature special issue on Jones, if you want to read some academic literary criticism on the subject.

But “The Fatigue” is also about what imperial violence and control cannot account for. Roman bureaucracy has its “most interior room,” from which orders roll down to the individual soldiers. But Christ, never named in the poem but everywhere present, “the gleaming Trophy” and “the Conqueror,” has already enacted his own rite in a private, upper room, instructing His disciples to receive His body and blood. Christ’s work in this apparently insignificant room is the greatest rebuke of empire and of violence—though elsewhere in The Sleeping Lord, he valorises the particularities of any beloved place or local culture as opposed to “ruthless, this-world domination” (26).

Jones says in his prefatory notes to “The Fatigue” that the poem intentionally recalls the liturgy of Holy Week, particularly the Tenebrae responsories for Maundy Thursday and Good Friday. This reliance on liturgical language points the reader back to the work of Christ, even as we are immersed in the work of the soldiers. The tension between the two gives me chills every time I read.

So all that to say, “The Fatigue” is a great poem. I hope you read it.

I hope you’ve had a week more restful than my own—but if you, like me, are feeling a bit frayed at the edges, I’m wishing you moments of peace and restoration.

Sarah